|

| http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2011-03/31/13806851_171n.jpg |

Commercialisation is the detachment of media outlets from political parties. It is the transformation of a state-owned organisation into a privately-owned corporate, which depends on advertising and other business activities for revenue. It is commonly identified that commercialisation will “foster liberalisation, establish or deepen democracy, and encourage the development of a globalised media culture” (Hadland, & Zhang, 2012). However, this is not the case for China. Some extreme opinions argue that commercialisation causes destructive consequences to China, both politically and socially (Hadland, & Zhang, 2012).

|

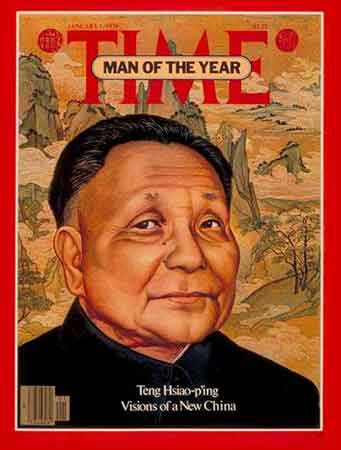

| Cover of TIME Magazine (January 1, 1979) http://politics.people.com.cn/mediafile/ 200812/12/F200812121452017765283982.jpg |

In 2007, the Chinese media market was the home to “2137 newspapers, 8000 periodicals, 290 radio stations, 420 television stations, and 400 million” Internet users (Hadland, & Zhang, 2012), being the “largest newspaper market in the world, selling more than 85 million copies daily” (Hadland, & Zhang, 2012).

Yet, the commercialisation did not offer Chinese media editorial independence. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) implemented measures to make certain that information reaching the public will not motivate people to challenge the party (Shirk, 2011). Specifically, organisations should be attached to government departments (Hadland, & Zhang, 2012). The state retains its position as the major shareholder of all newspapers and the owner of all television stations (Hadland, & Zhang, 2012; Shirk, 2011). The industry receive directives daily from propaganda departments, on what should or should not be reported, while media agencies also perform self-censorship to avoid negative consequences resulting from unfavourable reports (Hadland, & Zhang, 2012).

The CCP sees news media as an important component in the governance system, acting as the “propaganda” for the state (Bi, 2008). Aday and Livingston (2008) believe that media, in this structure, are too passive and weak for relying too heavily on Government sources, and are resistant to act as a “watchdog” (Xin, 2011). Without the Fourth Estate, Government’s operations are not supervised, allowing ineffective governance and social injustice. Moreover, audience will most likely doubt or even disregard information that they consider carry elements of propaganda (Bi, 2008).

Media censorship after the Tianjin explosion

It is not uncommon for the Chinese government to control and censor news reports after a major disaster or accident happens (Chan, 2015). Following the Tianjin explosion on August 12, 2015, one of the major debates around the nation was that whether the Government had released the accurate figure of fatality, which was reported in official television channels, newspapers and online media (Chan, 2015). Other unofficial reports and private investigations were strictly prohibited, as over 360 social media accounts were suspended or permanently shut down for “spreading rumours” by the Cyberspace Administration of China (Xinhua, 2015). 50 “rumour-mongering” sites were also investigated, from which 18 were revoked. The Premier Li Keqiang requested Government agencies to constantly disclose information so that rumours will stop flying (Dwyer, & Xu, 2015).

Worsening the situation, local television channels in Tianjin broadcasted no special news section on the morning following the explosion. “They [had] been preparing… special news reports together overnight continuously, but [were] only waiting for a green light” (Chan, 2015). Such passive and supine decision-making were condemned not only by citizens, but also media around the world (“China silences netizens”, 2015; Cheung, 2015). Ironic comments on social media such as “the world is watching Tianjin, but Tianjin is watching Korean soap” went viral and became International newspaper headlines (“Shijie zai kan Tianjin”, 2015).

|

| “The world is watching Tianjin, but Tianjin is watching Korean soap.” Television station did not announce latest injuries and fatalities figures for the whole morning-- Ming Pao News (August 14, 2015) http://news.mingpao.com/pns1508141439489156602 |

The Rise of Citizen Journalism

POV Community Engagement & Education (POV) (2013) defines citizen news as “unfiltered, independent, non-objective and diverse” information captured and distributed by citizens. This contemporary way of news reporting cater the needs of people who desperately seek up-to-minute information, especially during emergencies like the Tianjin explosion (Chan, 2015). In fact, a lot of footages broadcasted on TV news were captured by citizens. With citizen journalism, the speed of information circulation is too fast that it is beyond the Government’s control even if it wants to “cover up” information (Chan, 2015; Aday, & Livingston, 2008).

On the contrary, in some cases, citizen journalism did alter Government’s policies and actions (POV, 2013). Some of these successful cases are demonstrated in Xin’s (2011) chapter and Maing and Rodriguez’s (2012) documentary film High Tech, Low Life.

These successful cases are few and far between, but citizen journalists are willing to risk persecution to counter state-run media (POV, 2013). The Propaganda Department once sent a statement to national news agencies, prohibiting the coverage of a citizen journalist, Tiger Temple, “do not use terms such as citizen reporter… in other news as well” (Maing, & Rodriguez, 2012). Tiger Temple was once asked to leave Beijing during the New Year holiday because he “might cause trouble”, while Zola, another citizen journalist featured in the documentary, was also banned from leaving the country for a conference overseas (Maing, & Rodriguez, 2012).

|

| ZHOU, Shuguang (Zola) |

|

| ZHANG, Shihe(Tiger Temple) |

From the commercialisation of the media industry to the rise of citizen journalism, the way Chinese citizens receive and spread information has changed in recent decades. It is a change from a “one-to-many” system of mass communication, into an interactive sharing platform among the society (Song, 2015). As Bi (2008) argues, a thorough reform on the system that enhances the credibility of the mass media is essential and beneficial for both citizens and the Chinese government, in terms of the circulation of unfiltered and accurate information, as well as the effectiveness of governance. Nations around the world are now closely observing how the Chinese government comprehensively implement the “Four Civils Rights” (right to be informed, right to participate, right to express, and right to supervise) brought up by former president Hu Jintao (Bi, 2008).

REFERENCES

- Aday, Sean, & Livingston, S. (2008). Taking the state out of state-media relations theory: how transnational advocacy networks are changing the press-state dynamic. Media, War & Conflict, 1(1) 99-107. doi: 10.1177/1750635207087630

- Bi, Y. T. (2008, May 14). Xinwenmeiti gongnengxing chonggou de sikao [A reflection on the recomposition of the functionality of the news media]. People’s Daily Online. Retrieved from http://media.people.com.cn/BIG5/22114/42328/122711/7238574.html

- Chan, H. M. (2015, August 24). Reporting the Tianjin Explosion: Thoughts on the Chinese Media’s Performance [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.jomec.co.uk/blog/reporting-the-tianjin-explosion-thoughts-on-the-chinese-medias-performance/

- Cheung, E. (2015, August 13). CNN, local Chinese media struggle to report on Tianjin explosion. Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved from https://www.hongkongfp.com/2015/08/13/cnn-local-chinese-media-struggle-to-report-on-tianjin-explosion/

- China silences netizens critical of “disgraceful” blast coverage. (2015, August 13). British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-33908168

- Dwyer, T., & Xu, W. (2015, August 25). Tianjin disaster takes social news sharing to new levels in China. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/tianjin-disaster-takes-social-news-sharing-to-new-levels-in-china-46401

- Hadland, A., & Zhang, S. I. (2012). The “paradox of commercialization” and its impact on media-state relations in China and South Africa. Chinese Journal of Communication, 5(3), 316-335. doi: 10.1080/17544750.2012.701422

- Maing, S. (Director), & Rodriguez, T. (Producer). (2012). High Tech, Low Life [Motion picture]. The United States of America: Argot Pictures.

- POV Community Engagement & Education. (2013). Discussion Guide: High Tech, Low Life. Retrieved from the Public Broadcasting Service website: http://www.pbs.org/pov/hightechlowlife/discussion-guide.php

- Shijie zai kan Tianjin, Tianjin zai kan Han ju [The world is watching Tianjin, but Tianjin is watching Korean soap]. (2015, August 14). Ming Pao. Retrieved from http://news.mingpao.com/pns1508141439489156602

- Shirk, S. L. (2011). Changing Media, Changing China. In S. L. Shirk (Ed.), Changing media, changing China (pp. 1-37). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Song, J. W. (2015, June 6). Meitiren de zhuanxing fangxiang he juese zhuanhuan [The transition of roles carried by media practitioners]. People's Daily Online. Retrieved from http://media.people.com.cn/n/2015/0602/c396602-27091652.html

- Xin, X. (2011). Web 2.0, citizen journalism and social justice in China. In G. Meikle, & G. Redden (Ed.), News online: transformations and continues (pp. 178-194). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.Xinhua. (2015, August 15). Social media accounts closed for spreading rumors about blasts. China Daily. Retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015-08/15/content_21606460.htm

2 comments:

Hey Winmy,

What ?! you blog !?

That's the funniest in this week.

What's the funny part?

Post a Comment